When Pacific island leaders gathered in Nauru this month, they issued a security declaration affirming climate change as the “single greatest threat” to the region.

That climate change is a threat to Pacific islands is in some ways obvious; indeed the climate change wording in the “Boe Declaration on Regional Security” was derived from previous Forum leaders’ communiques. What is new is the explicit recognition, in a security declaration, that climate change is the single greatest threat to the region.

Leaders from Pacific islands have long campaigned for recognition of climate change as a security issue.

Leaders from Pacific islands have long campaigned for recognition of climate change as a security issue, and particularly as a threat to the survival of low-lying atoll nations. In 1991, for example, Pacific leaders warned that global warming and sea level rise placed the cultural, economic and physical survival of Pacific nations “at great risk”. Over the decades since, they have lobbied at the United Nations for climate change to be understood as a security threat. As a bloc, Pacific island states want the UN Security Council to appoint a special rapporteur on the security threats posed by climate change.

A growing challenge

The US representative at the Forum meeting, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, sought to convince Pacific island leaders that North Korea posed the greatest regional threat. Others, particularly Australian politicians, are concerned that China may use “debt diplomacy” to undermine the sovereignty of Pacific island states. Despite these concerns, and other issues detailed in the declaration (such as cybersecurity and transnational crime), island leaders were adamant the Boe Declaration should emphasise the challenge posed by climate change.

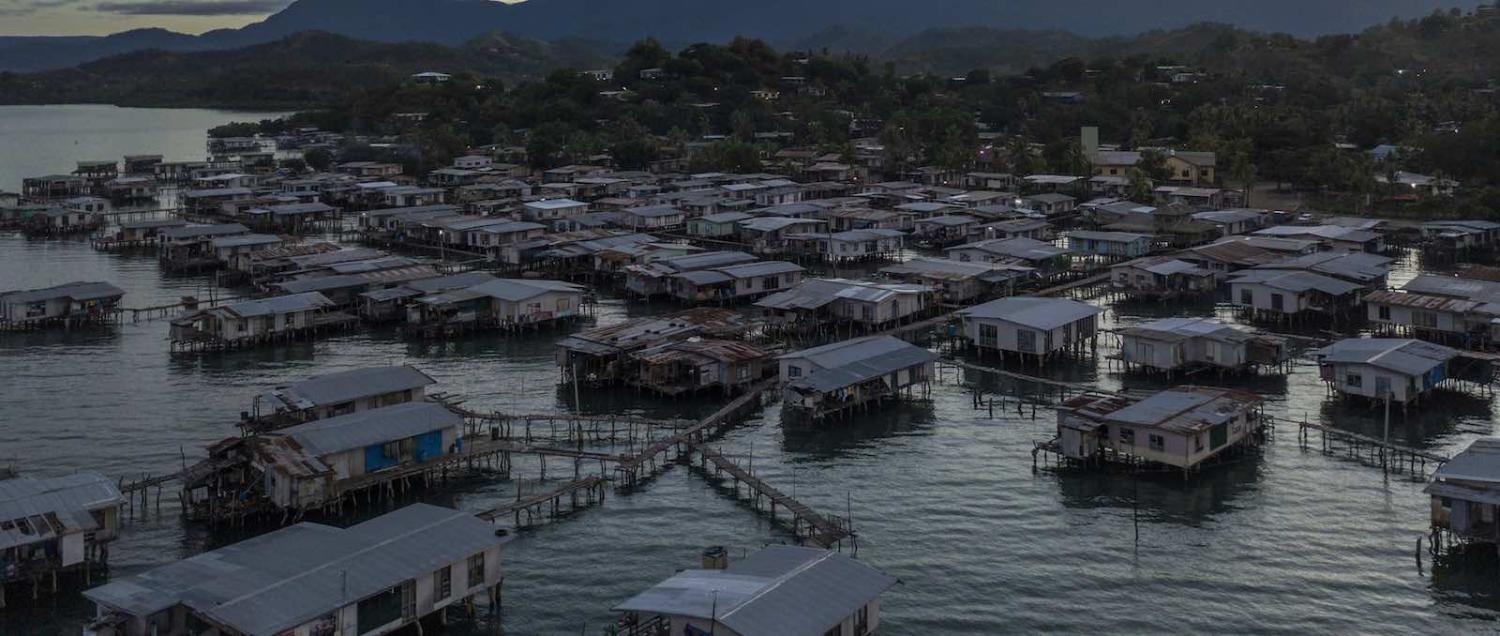

The threats posed by climate change are manifold, and are already being felt in the Pacific. This includes stronger cyclones, changing rainfall patterns, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, sea-level rise and coastal inundation.

A warmer ocean provides more fuel for cyclones, and recent years have seen the strongest cyclones ever to make landfall in the Pacific. Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu (2015) and Cyclone Winston in Fiji (2016) are windows on the future. Both storms caused unprecedented damage, leaving thousands homeless and laying waste to schools, medical centers and crucial infrastructure. Most tragically, the storms claimed dozens of lives.

Sea-level rise presents a threat to the territorial integrity of Pacific states. A study commissioned by the US military, published in April, has found that sea-level rise will make dozens of low lying Pacific islands uninhabitable by the middle of this century as salt-water intrusion undermines access to drinking water.

Of course, it is not only Pacific islands that face threats associated with climate change. A decade ago, then Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd identified climate change as a “fundamental national security challenge”. This year, in May, a senate inquiry found that climate change is “exacerbating threats and risks to Australia’s national security”, and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres argues climate change represents a “direct existential threat” and a challenge to “the security of nations”.

Addressing root causes

Tackling climate change requires global cooperation to reduce carbon emissions. Toward that end, the Boe Declaration reaffirms a commitment to “progress implementation of the Paris Agreement”. Progress is sorely needed.

Current pledges under the Agreement put theworld on track for 3°C of warming this century; a catastrophic trajectory for island states (and for the rest of the world). It is not surprising that Pacific islands are leading multilateral efforts to increase the ambition to tackle climate change. Fiji is currently president of climate talks at the UN, and has convened a year-long “Talanoa Dialogue” to encourage states to pledge greater emissions reductions. Marshall Islands President Hilda Heine has launched a “Declaration for Ambition”, and will host a global summit in November intended to generate more ambitious pledges before 2020.

A key problem for the Pacific Islands Forum will remain the policies of the largest member of the grouping. Australia has pledged “low-ambition” targets under the Paris Agreement, and is not currently on track to meet those targets (indeed, at present, Australia’s emissions are rising). Australia is also the world’s largest coal exporter, and will soon be the world’s largest gas exporter.

This commitment to fossil fuels has drawn the ire of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretary General Dame Meg Taylor who, in a speech in Canberra, explained that Australia’s promotion of coal-fired power is out of step with other Forum members, and places the “wellbeing and potential” of the region at risk.

To meet the challenge of climate change, all Forum states will need to reduce their carbon emissions, and to move from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Regional cooperation should complement and strengthen global efforts to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. This could encompass a regional “net-zero emissions” target by 2050. New Zealand has set such a target domestically, and a regional target would drive ambition consistent with meeting the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

The Boe Declaration would also be strengthened significantly if the Pacific Islands Forum establishes a committee to report regularly on the security implications of climate change in the Pacific islands.